Modernism: From the Heroic to the Everyday

The following is based on the presentation given by Dr. Jiat-Hwee Chang at the Docomomo Singapore official launch on 13 October 2021

(The text and images in the following are partly drawn from the forthcoming book Everyday Modernism: Architecture and Society by Jiat-Hwee Chang and Justin Zhuang with photographs by Darren Soh that is scheduled to be published by Ridge Books in 2022.)

Good evening everyone. Thank you very much for taking time to join us at our official launch.

As you might know, the full name of Docomomo is a long one—International committee for documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the modern movement. Only four words from the long title are abbreviated to form our acronym Docomomo—documentation, conservation, modern, and movement.

Hence, documentation is one of the keywords of the organisation. It represents an important part of what we do. And it is central to our mission of conserving the modernist built environment. It is also what I will focus on in this presentation.

Modernist 100

One of ways we share the results of our documentation is through our website, mainly under the list of Modernist 100. Modernist 100 is given a prominent place on our website. It appears on our landing page, right below our mission statement

I would like to say two things about the website before I move on to discuss Modernist 100. First, it is a collective effort with the contribution of many people, all of them are acknowledged in detail on the website. Many of them are here at the launch. Second, the website is a work in progress. It’s incomplete. So we welcome contributions. Please talk to us if you have ideas. It might also have errors despite our best efforts. And if you spot any error, please tell us.

Modernist 100 is a database of 100 representative modernist buildings in Singapore. The number is a rough guide and not an absolute figure. We currently have 42 entries on our website. Our intention is to slowly increase the number of entries to reach 100, a number that we already have in an initial spreadsheet. But we might eventually exceed 100 buildings. On that note, we would like to add that we welcome your suggestion on what to include.

You might ask: How did we arrive at our 100 buildings? What are our selection criteria?

We started by consulting the existing key texts on modern architecture.[1] We also went through unpublished PhD theses, older journals, and referred to resources put up by the URA & PSM.[2]

Therefore, the Modernist 100 list unsurprisingly has a few familiar iconic buildings,. These range from the yet to be officially conserved Golden Mile Complex[3] and the threatened People’s Park Complex, to the beautifully conserved Jurong Town Hall and the sadly demolished Pearl Bank Apartments.

Heroic Modernism

We call these familiar icons “heroic modernism”. By heroic, we take reference from 2 sources. The first is Alfred Wong’s use of word heroic in a 1998 essay to describe the period in the 1960s and 1970s, when the local architectural profession was entrusted with the task to transform Singapore after its independence and lay the foundation for this modern metropolis.[4] The second is Mark Pasnik, Michael Kubo and Chris Grimley’s beautifully written and illustrated book Heroic.[5] In the book, the authors see the label brutalism as a misnomer for the type of architecture that remade Boston in the mid-20th C. Instead of brutalism, they choose to describe these buildings and the vision behind them as heroic.

We share their appreciation of the vision behind these local brutalist buildings and we use the term heroic modernism as our homage to the planners, architects, developers and builders that realised these icons.

Everyday Modernism

Besides the familiar, our Modernist 100 list also has quite a number of less familiar buildings that tell forgotten stories of Singapore’s modernism. We call these less familiar buildings our “everyday modernism”.

An example is the Circular Point Block at 259 Ang Mo Kio Ave. 2. This is the only circular point block in Singapore. The building speaks of the typological exploration and innovation being carried out by the HDB in the 1980s. It was one of the seven new typological designs published by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in the August 1979 issue of Our Home magazine.

Besides housing, HDB towns also have amenities in order to be self-sufficient. While the flats are based on standardised types, the amenities have different designs. One of the amenities is a swimming complex. The first one was completed in Queenstown in 1970. The example we included in Modernist 100 is the Ang Mo Kio Swimming Complex, completed in 1982. Like the demolished Bedok swimming complex that was completed a year before it, it has a sculptural roof form that serves as a 5th elevation for the high-rise flats around.

A type of recreational amenity in HDB towns that is probably better known is the HDB-designed playground. Built mainly in the 1970s and 1980s, these were designed by Khor Ean Ghee, an interior designer working for the HDB. These playgrounds started off as simple animal shaped structures, like those of tortoise and pelican, made from prefabricated concrete pipes. They later became more complex structures cladded in mosaics like the dove and dragon playgrounds launched in 1979.

Another entry in our list is the Park Road Development, which consists of a few connected HDB podium-tower blocks. The development is a forerunner of other podium-tower mixed-use developments by the HDB.

Other than buildings planned and designed by the HDB, we also include those conceived by other government agencies. One of them is the Public Works Department (PWD).

In our list, we include a school typology with hexagonal classrooms. This was one of 10 winning designs from a 1975 internal competition jointly organised by the Ministry of Education and the PWD to increase the variety of school designs and to move away from what a journalist described rather harshly as “box-like structures with no beauty or character.”[6] This was the only winning design submitted by a female architect. In this case a Thai architect working for the PWD by the name of Puangthong Intarajit. The design was used for at least 3 schools located at Ang Mo Kio, Henry Park and Alexandra Road.

Another entry, 63-66 Yung Kuang Road, better known as the diamond blocks, is probably not that unknown. An instagrammer favourite, the building was designed by another government agency, the Jurong Town Corporation and completed in 1973 as a part of the Taman Jurong housing estate.

Everyday modernism also happens to be the title of a book that Justin Zhuang, Darren Soh and myself are working on. So I would also take this opportunity to shamelessly plug the book.[7]

It’s a collection of 33 essays that look at a whole array of building types that changed the way we live, play, work, travel, connect, and pray. They range from the first condominium to the first columbarium. They are spread across different scales, including both small HDB playgrounds and large landscape like the East Coast Park. They include not just buildings and landscapes but also infrastructure like pedestrian overhead bridge and the Pan Island Expressway

The publication of the book is funded by a Heritage Grant from the National Heritage Board and the expected publication date is mid next year.

The Case for Everyday Modernism

I thought I would spend the rest of this presentation making a case for everyday modernism. One of the questions we ask ourselves is why is everyday modernism under the radar and less familiar?

Could it be that the buildings of everyday modernism were planned and designed by organisational men and women in public agencies like HDB, JTC and the former PWD? Unlike buildings by architects in private practice, these buildings are usually not attributed to any individual architects but to organisations.

Without a known architect, there is no design authorship, which make it more difficult to include in conventional architectural discourse that tends to celebrate masterpieces and master architects.

Moreover, most everyday modernist buildings are located not in the city centre, but in HDB estates. As part of our everyday environment, they are perhaps more likely to be overlooked. But as 80% of Singapore population live in public housing estates. These estates have the largest stock of modernist buildings. By ignoring everyday modernism, we are also neglecting a significant proportion of our built environment.

The Everyday and The Heroic

Although we created the two categories of heroic modernism and everyday modernism, they are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they are intertwined in many ways.

For one, architects in private practice who have designed heroic modernist buildings are frequently involved in the design of everyday modernist buildings as well. Tay Kheng Soon, for example, designed both Golden Mile Complex (when he was with the Design Partnership) and HDB flats at Choa Chu Kang (when he was with Akitek Tenggara).

In addition, when a style or aesthetic tendency took root in heroic modernism, it often also spread to everyday modernism. For instance, we see that both the former subordinate courts and the former HDB office at Teck Ghee were being executed in the same brutalist language popular in the 1970s.

The Urban Reform in 1960s and 1970s

And if we look at the urban history of Singapore, we also see that the urban renewal in the city centre and the building of satellite towns of public housing in the outlying areas were closely interconnected.

A key aspect of urban renewal was the government sales of site programme and many of the heroic modernist buildings were built on the sites sold through this programme.

Public housing was essential to accommodate the population affected by urban renewal. It was the success of the first 5-year plan of the HDB that enabled urban renewal to begin in the late 1960s.

The base diagram that made up the top two drawings is taken from the first concept plan launched in 1971. But its assumption of treating the whole of Singapore as a single urban entity stretched back to the ring concept (bottom middle image) first put forward by the United Nations experts Otto Koenigsberger, Charles Abram and Susumu Kobe in 1963, which radically altered the older 1958 colonial masterplan (bottom left image) that had a distinct urban-rural divide.

Hence, one can say that both heroic and everyday modernism are products of the urban reform of the 1960s and 1970s.

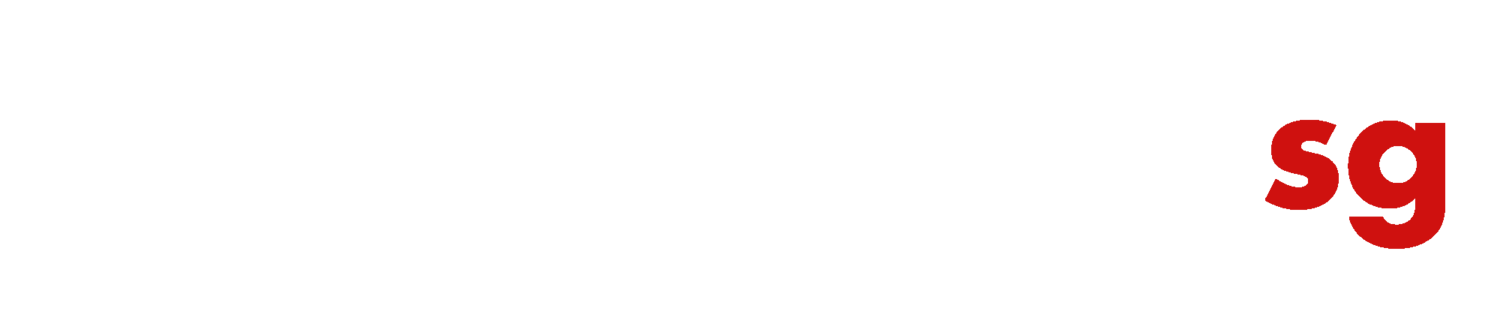

Modernism as Our Living Vernacular

Because of our unique urban history and the twin success of our urban renewal and public housing, one could say that Singapore’s modernism is unlike that in many other places.

Not only does it constitute a very, very large proportion of our built environment, it is, unlike in some parts of Europe and North America, not seen as the negative opposite to a local vernacular and thus stigmatised. Rather, modernism in Singapore is well-loved.

In fact, for the post-1970s generations, modernism is our vernacular, a living vernacular.

Overcoming Obsolescence

But like all built environment in Singapore, both heroic and everyday modernism are also bounded by the same fate of obsolescence. Although the driving forces behind their demise might differ, both are precarious in this land scarce nation that is constantly remaking itself.

If we see everyday modernism as our vernacular and if we regard it as important, how do we begin to delay or even overcome its fate of obsolescence? How do we begin to calibrate or recalibrate our value so that the price of demolishing everyday modernism is demonstrably greater than cost of rejuvenating them?

Building Significance

One way is of course to re-value and re-evaluate the notion of significance of our built environment.

In the traditional heritage discourse, the significance of a building comes from its form and construction. Questions such as how unique is the form and how innovative is the construction of a building are considered important. We ask these questions too. That’s why we include examples like OCBC Centre in our list.

Intended Use

Besides form and construction, we would like to introduce the seemingly utilitarian category of use as another criteria in evaluating significance.

Use in traditional heritage discourse tends to be associated with buildings where major and significant political and social events have taken place. We do not disagree, which is why the Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House is in our list.

But we are also interested in the notion of use in the minor and quotidian sense and not just in the major and grand sense.

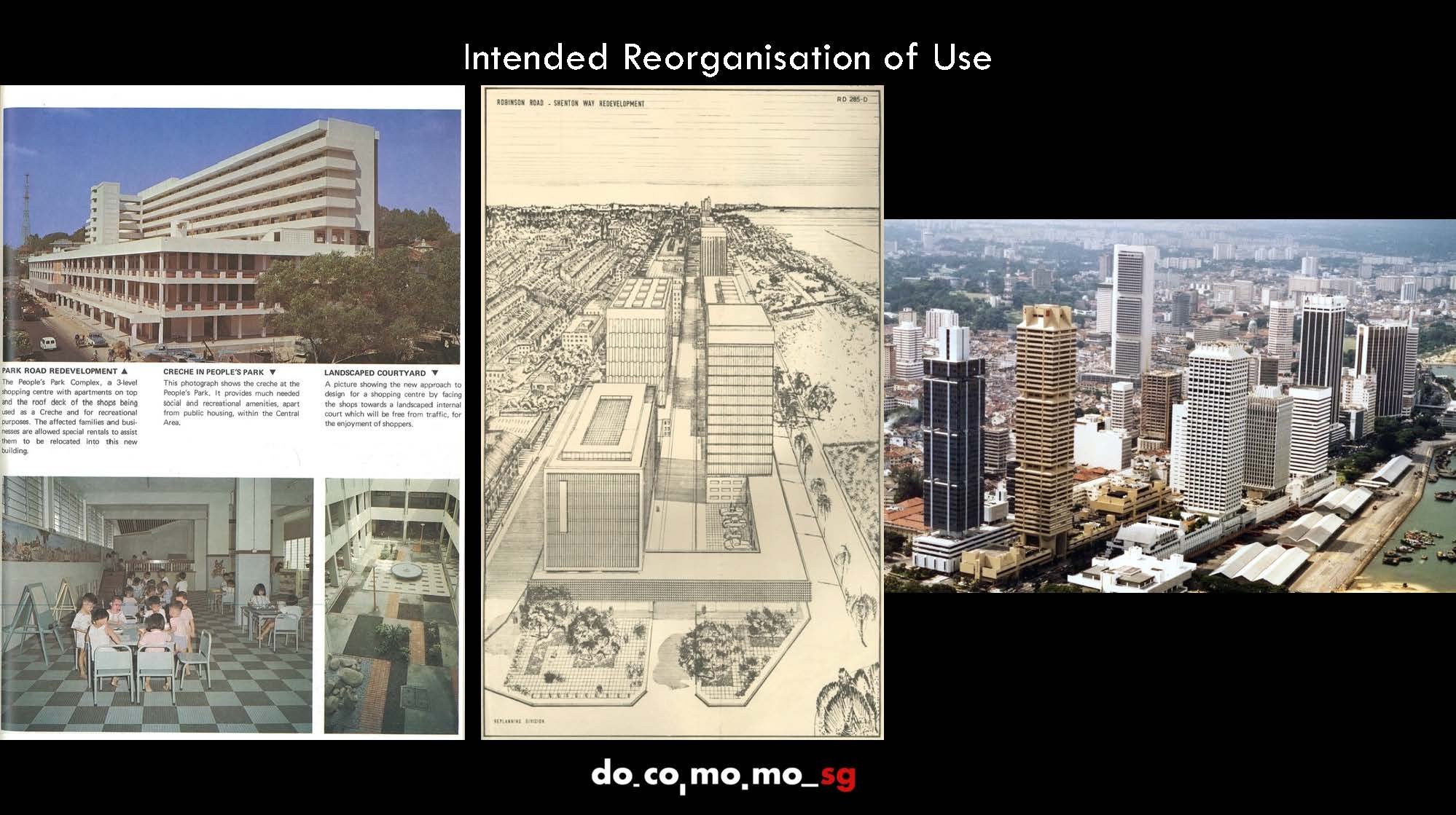

We all know that modernism is known for introducing new building typologies that spatially reorganise how occupants use spaces.

In Singapore, such intended reorganisation of space was central to our urban reform and socio-economic development in the 1960s and 1970s. For example, the population was moved from shophouses and kampong houses in the city centre and the urban fringes to high-rise public housing in satellite towns, radically reconfiguring the spatial patterns of their everyday lives.

In the city centre, the podium tower block was the typology applied to residential, office and commercial complexes. It changed not just the way we live, but also the way we work, shop, and recreate.

Transient and Routine Use

Besides changes in use intended by planners and architects, there are also other forms of use with very different relationship to agencies, time and space.

Uses that are transient might also be important. Especially if the transient uses take on a rhythm and become a routine. These types of use might be unintended but they are central to creating a sense of belonging, turning an empty space into a meaningful place.

Modernist buildings—with elements like void decks—are especially accommodative of and open to different types of intended and unintended uses.

Change in Use

Modernist buildings sometimes also accommodate changes at a different time scale.

Some like the former Metropole Cinema, that was designed by Wong Foo Nam’s firm and opened in 1958, was converted into a Methodist Church in 1985.

The fall in attendance in the local cinema industry that coincided with the increase in Christian denominations looking to set up their own churches in the 1980s meant that the Metropole was one of many such examples of cinemas being converted into churches at that time.

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Another form of change can be seen at the Tan Boon Liat Building. Sited on what was once a collection of godowns owned by an eponymous rattan merchant, the flatted factory was completed in 1976.

That was a time when Singapore has successfully embarked on industrialisation and when Singapore River’s port activities began to diminish with the rise of container shipping.

In the 2000s, Tan Boon Liat Building would witness another round of transformation. From a flatted factory, it evolved into an “unofficial Furniture Mall” and a “hot spot for local furniture hunters.” In the mid-2010s, it boasted more than 30 furniture stores offering what a journalist called the “Tan Boon Liat Lifestyle.”

Building Biographies

Once we look at the histories of these building closely, we begin to realise that a building is not a static entity. Like a person, a building has many stages of existence, from birth, to growth, to maturing, to aging and finally death. All these stages are intimately bound up with wider social, cultural, economic, and political processes.

Seen in this light, our documentation is not unlike writing building biographies. We understand how a building could decline through neglect (and the lack of maintenance) and die a premature death like the Pearl Bank Apartments and some other strata titled buildings.

Likewise, a building could also have a long and healthy life with constant care and maintenance. Even a dying building could be rejuvenated with intensive care, some love and imagination.

Our interest in biographies is not just with the heroic or the great men (and women) but also with the ordinary folks that make up society.

In a through-and-through modernist environment like Singapore, writing building biographies of the heroic modernism and neglecting those of the everyday modernism seem both incomplete and inadequate.

Documentation is a prerequisite for Conservation. More documentation would hopefully lead us to better understandings and more inclusive conservation.

Conclusion

To sum up, our documentation seeks to enlarge the types of agents in the making of our modernist built environment and the forms of agencies taken into consideration.

We would also like to expand the types and varieties of modernist buildings beyond a few exemplars of heroic modernism.

And the stories that we tell about them should extend beyond their moment of “completion” to embrace changes, alterations and rejuvenations.

By multiplying the stories, we hope to create more conversations with different stakeholders.

Thank you.

[1] Norman Edwards and Peter Keys, Singapore: A Guide to Buildings, Streets, Places (Singapore: Times Editions, 1988); Weng Hin Ho, Dinesh Naidu, and Kar Lin Tan, Our Modern Past: A Visual Survey of Singapore Architecture, 1920s-1970s (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society and SIA Press, 2015); Yunn Chii Wong, Singapore 1:1 City: A Gallery of Architecture and Urban Design (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2007); Yunn Chii Wong, Singapore 1:1 Island: A Gallery of Architecture and Urban Design (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2007).

[2] The journals included Rumah and SIAJ. And the PhD theses are Eu-jin Seow, “Architectural Development in Singapore” (Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Melbourne, University of Melbourne, 1973); Jon Sun Hock Lim, “Colonial Architecture and Architects of Georgetown (Penang) and Singapore, between 1786 and 1942” (Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Singapore, National University of Singapore, 1990).

[3] The Golden Mile Complex was officially gazetted for conservation slight more than a week after the launch on 22 October 2021. See Keng Gene Ng, “Golden Mile Complex Gazetted as Conserved Building; Future Developers to Get Building Incentives,” The Straits Times, October 22, 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/golden-mile-complex-gazetted-as-conserved-building-future-developers-to-get-building.

[4] Alfred H. K. Wong, “A Brief Review of Our Recent Architectural History,” in Contemporary Singapore Architecture, ed. Singapore Institute of Architects (Singapore: Singapore Institute of Architects, 1998), 252.

[5] Mark Pasnik, Michael Kubo, and Chris Grimley, Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2015).

[6] Teresa Ooi, “Look at Our Schools of the Future,” New Nation, August 21, 1975.

[7] Jiat-Hwee Chang, Justin Zhuang, and Darren Soh, Everyday Modernism: Architecture and Society in Singapore (Singapore: Ridge books, 2022).