Capping Modern and Tradition: The “Revolutionary” Roof of the Singapore Indoor Stadium

Written by Justin Zhuang based on an interview with Paul Tange and Yashuhiro Ishino of Tange Associates on 7 June 2024.

The Singapore Indoor Stadium soon after it was completed.

COURTESY OF TANGE ASSOCIATES

Some have likened it to a traditional Japanese hat. Others see the outlines of a Star Destroyer spaceship from the futuristic movie Star Wars. Without a doubt, the roof of the Singapore Indoor Stadium is one of—if not, the most—distinguishing feature that has made it a familiar icon along the Kallang Basin today.

The design first arose almost forty years ago when Japanese architect Professor Kenzo Tange was appointed by the Singapore government to partner Singapore-based RSP Architects Planners & Engineers to help develop an indoor stadium in 1985. He and his team, including Yasuhiro Ishino and Paul Tange, his son, set about coming with a building that would blend in with its waterfront location then shared with the former National Stadium and other attractions such as the Wonderland Amusement Park and the Oasis Theatre Restaurant Niteclub and Cabaret.

Tange had previously designed another indoor stadium for Japan when it hosted the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. The Yoyogi National Gymnasium was renowned for its dramatic curved roof form that was suspended simply by wire ropes strung between two structural support columns some 126 metres apart. The design, said to be the world’s largest suspended roof span when it first opened, created a column-less interior for its 15,000 spectators to enjoy a shared experience. This was one of the goals for the 12,000-seater indoor stadium in Singapore too, says Paul, who is the chairman of Tange Associates today.

“For my father, what’s important in the Yoygoi stadium was to create one column-less space and you can feel the people inside share that space. That is the main spatial desire my father had,” he adds.¹

“In the indoor stadium, it’s a different (roof) system but the philosophy of the space is the same. It is one space shared by athletes and also the audience and they can see each other and get excited.”

The Yoyogi National Gymnasium (left) and its interior (right).

COURTESY OF TANGE ASSOCIATES

Prototypes of the various roof forms explored for the Singapore indoor stadium

COURTESY OF TANGE ASSOCIATES

Although Singapore wanted a similar space for its indoor stadium, the Yoyogi’s suspension structure was challenging to construct and unsuitable for the soft clay soil of the waterfront site, according to Ishino. Tange began considering alternative roof systems and the team explored more than 20 designs before shortlisting four that were presented to a committee led by then First Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, Second Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong and National Development Minister Teh Cheang Wan.² Ishino recalls it was eventually down to a round roof similar to Western-style domes like the Pantheon in Rome, or a diamond-shaped design with sloping forms that were inspired by temples from China and Japan. The committee eventually chose the latter as it was more unique.

Model of the selected diamond-shaped roof.

COURTESY OF TANGE ASSOCIATES

“We were trying to find an Asian-style curved roof that is not just traditional but in a modern style. That’s why we designed the diamond-shaped roof and material is stainless steel so it looks more new and modern,” explains Ishino, who is the now president of the company.³

At the time the S$68-million design was unveiled to the public, the senior Tange explained that “the design has an oriental-look befitting the Singapore context and skyline”.⁴ He later added that it was “the perfect foil against the Central Business District skyline” in the background, which included rectilinear modern skyscrapers such as the OCBC Building by I.M. Pei and Tange’s own OUB Centre (now Raffles Place Tower 1).⁵

Despite being an outsider to the Singapore architecture scene, Tange’s approach of blending traditional roof forms with modern materials echoed similar local trends at the time. One of which was how Housing and Development Board architect Asadus Zaman revived the historic Nusantara model of mosque with its three-tiered tajug roof in his design for the Darul Aman Mosque (1986). Another was the way Akitek Tenggara led by Tay Kheng Soon modernised the traditional Chinese temple with a copper-cladded pyramidal roof supported by a steel space frame structure in the Chee Tong Temple (1987).

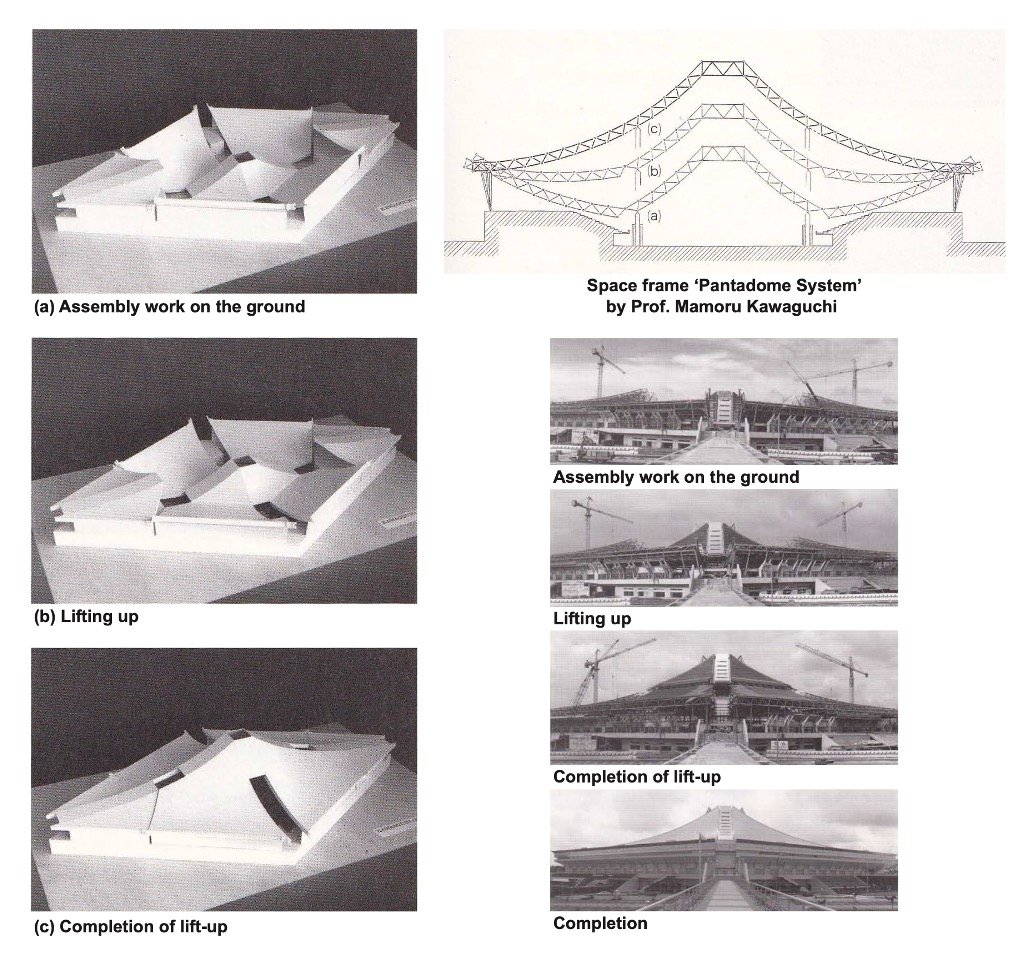

Besides its distinctive design, the indoor stadium’s roof was a “revolutionary idea in stadium construction” that did away with the “jungle of scaffoldings” typically required.⁶ Tange and his team worked with Japanese engineer Professor Mamoru Kawaguchi to use his Pantadome system that integrates the geometry and mechanism of its structure with its erection process, and had previously been used to construct Japan’s World Memorial Hall in Kobe and the Barcelona Indoor Stadium. In the case of the Singapore Indoor Stadium, its 200-by-120-metre curved roof made of space frames from Nippon Steel was first assembled on the ground after the stadium’s concrete base was complete. The structure was then lifted by the control of computers to ensure an even keel, rising about four metres a day from a level of 20 metres to its full height of 45 metres before the hinges on three lines of its surface were locked in place.⁷ The hoisting of the roof was completed in just one week in February 1989.⁸ It is likely why the delivery for the stadium could be cut to three years instead of the five originally planned for.⁹ In fact, the stadium’s South Korean contractor Sanyang eventually completed the project two weeks of schedule.¹⁰

Section showing the indoor stadium’s 39m ceiling height and 120m width.

COURTESY OF TANGE ASSOCIATES

Section showing the indoor stadium’s 200m length.

COURTESY OF TANGE ASSOCIATES

On 31 December 1989, the indoor stadium was officially opened by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew with the simple push of a button.¹¹ This was followed by an hour-long musical extravaganza, My Country, My Singapore, which chronicled the country’s three decades of statehood since it gained self-governance from the British in 1959—a fitting opening for the shiny new landmark that capped the successful modernisation of Singapore and its entry into a new era.

Illustration of the construction of the indoor stadium.

COURTESY OF KAWAGUCHI & ENGINEERS

Paul Tange and Yasuhiro Ishino, Interview with Paul Tange and Yasuhiro Ishino, 7 June 2024.

Joe Dorai, ‘Stadium Ready in Three Years’, The Straits Times, 22 April 1986.

Tange and Ishino, Interview with Paul Tange and Yasuhiro Ishino.

Joe Dorai, ‘Stadium Ready in Three Years’.

Helen Chia, ‘Tange Thinks Big’, The Straits Times, 8 January 1990, sec. Section Two.

Joe Dorai, ‘Stadium Ready in Three Years’.

Agnes Wee and Judy Tan, ‘The Top Will Take Shape on the Ground’, The Straits Times, 24 April 1986.

Joe Dorai, ‘Indoor Stadium Will Be Ready Ahead of Time’, The Straits Times, 1 March 1989.

Joe Dorai, ‘Stadium Ready in Three Years’.

Joe Dorai, ‘Indoor Stadium Will Be Ready Ahead of Time’.

Martin Soong, ‘Celebrating Singapore’s Singular Spirit’, The Business Times, 1 January 1990.

Cover image by Darren Soh